Here’s a simple task to turn your experience inward and discover what’s important to you:

Start with identifying what it is that you do at the very heart of your role as a leader. Consider the essence of your leadership, not just your tasks. Consider a metaphor that sums up who you are as a leader and as a person that is inextricably linked to your what!

Then look at why you’ve found yourself on this path.

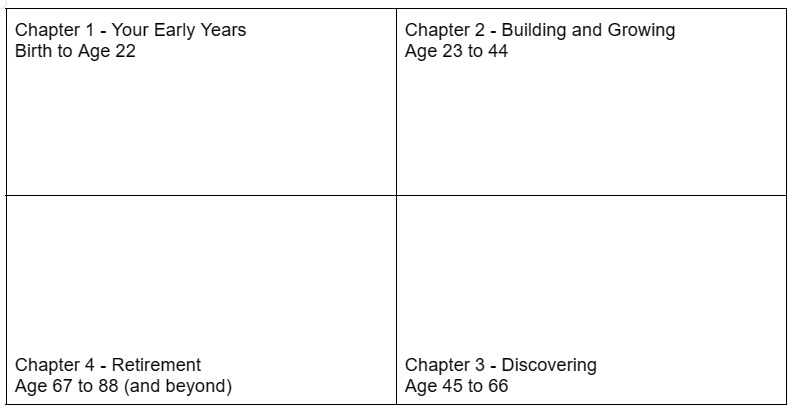

Next, explore how your knowledge can help you build a roadmap through life transitions you’ll face up ahead whether or not you’ve prepared. Consider these questions:

- Will you be leading teams right up until you decide you have something more you want to do?

- Will you view your current state as a stepping stone to something that is calling you?

- Are you even aware there may be a calling you’re not hearing because of all of the noise that gets in your way?

Taking the time to look into planning your own life, will support you in more effectively planning a new life (future state) in which your team will do their work, accomplish their tasks, and achieve their personal goals.

Next learn how to Build a Ship.